Cybernet Entertainment, a/k/a “The Fuck Brief” Case

Attorney

Case Overview

Marc Randazza represented Cybernet Entertainment, LLC (now known as kink.com) in a proceeding over the trademark “FuckingMachines” before the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). The colloquially known “Fuck Brief” was dubbed “one of the most entertaining legal documents you’re likely to come across” by the Orlando Weekly.

The brief was some of Randazza’s earliest work at the confluence of freedom of expression and intellectual property law, an academic interest that culminated in his LLM thesis: Marc J. Randazza, Freedom of Expression and Morality-Based Impediments to the Enforcement of Intellectual Property Rights, 16 Nev. L.J. 107 (2015).

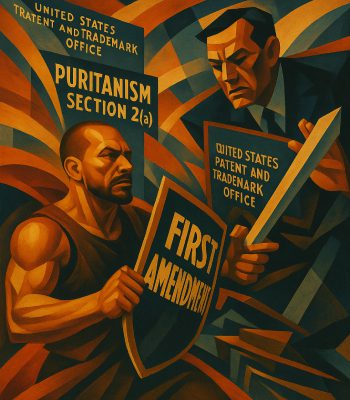

The Fuck Brief blended serious constitutional arguments with dash of rhetorical irreverence challenging the USPTO’s rejection of the “Fucking Machines” trademark as “immoral” or “scandalous.” Though the brief didn’t sway the examiner, its legal theories were vindicated by the U.S. Supreme Court in Matal v. Tam (2017) and Iancu v. Brunetti (2019).

The Battleground: A Trademark Clash Over Expression

Cybernet Entertainment sought to register “fuckingmachines” for its adult entertainment website, only to be rebuffed in July 2005 by USPTO examiner Michael Engel, who branded the term “fucking” an “offensive and vulgar reference to the act of sex.” Citing Section 2(a) of the Lanham Act—a dusty 1905 statute—the rejection threatened Cybernet’s ability to safeguard its brand. Enter a brief that was equal parts legal treatise and cultural manifesto, arguing that the USPTO’s moralistic stance was not only misguided but unconstitutional.

A First Amendment Issue

Randazza grounded his arguments in free speech, invoking Cohen v. California (1971), where the Supreme Court upheld “fuck” as protected expression. He contended that the USPTO’s rejection reflected an archaic moral framework out of step with modern culture. “The word ‘fuck’ appears in most dictionaries,” he writes, “and enjoys a variety of meanings and uses beyond sexual intercourse.” To prove it, he cited its ubiquity in films like Wedding Crashers and Casino, arguing that a word so woven into the cultural fabric cannot be deemed scandalous.

“The word may be used to express a strong emotion regarding a situation or event, as in ‘abso-fucking-lutely’ or ‘un-fucking-believable.’ It is a word of force that can assist us in our expressions of joy when used as an infix, as in ‘fan-fucking-tastic.’” This strategic reframe positioned “fuck” as a versatile term with commercial value, worthy of trademark protection in the context of Cybernet’s services.

Trademark Law Precision

Beyond free speech, Randazza argued that the USPTO misapplied Section 2(a) by ignoring the mark’s commercial context. “Fuckingmachines” is a descriptive brand identifier for Cybernet’s adult entertainment services, not gratuitous profanity. He insisted that trademark law requires evaluating marks as they function in the marketplace, not as abstract moral triggers. Context, paired with constitutional arguments, sought to bring a common sense and constitutional approach to an issue that Randazza himself said was unlikely to succeed, at the time, but he felt that the future would eventually topple the statute that permitted the USPTO to act as “morality police.”

Vindication in Tam and Brunetti

The USPTO upheld its rejection in 2008, and the “fuckingmachines” mark was abandoned because the client did not wish to pursue the action. But the theories were not defeated. Randazza stayed on top of attacking Section 2(a), writing about it in his CNN legal Column, “Decision on Asian-American band’s name is wrong” (2015).

And when the issue reached the Supreme Court, the First Amendment Lawyers’ Association (FALA) retained Randazza to file its brief, trying to persuade the justices to do away with the censorship regime.

The Supreme Court’s rulings in Matal v. Tam and Iancu v. Brunetti confirmed the brief’s core arguments. In Tam (2017), the Court struck down the Lanham Act’s disparagement clause, ruling that the USPTO’s denial of “The Slants” violated the First Amendment. Justice Alito wrote, “Speech may not be banned on the ground that it expresses ideas that offend”—a direct echo of The Fuck Brief’s challenge to moral gatekeeping.

Iancu v. Brunetti (2019) went further, invalidating Section 2(a)’s “immoral or scandalous” bar—the very provision used against “fuckingmachines.” Upholding Erik Brunetti’s mark “FUCT,” Justice Kagan declared, “The government may not discriminate against speech based on the ideas or opinions it conveys.” This ruling mirrored Randazza’s arguments that the USPTO’s rejection was an unconstitutional judgment on expression, not a neutral trademark decision.

The Fuck Brief did not succeed, but it was vindicated and finally Section 2(a) fell.

Case Documents

Note: The “Fuck Brief” is accessible via the USPTO’s website under In re Cybernet Entertainment, LLC, Serial No. 78666564. See also Matal v. Tam, 582 U.S. 218 (2017), and Iancu v. Brunetti, 139 S. Ct. 2294 (2019)