If you ever wonder why court cases take so long to resolve, maybe it is because sometimes the courts are bogged down in really silly lawsuits like this one.

But, silly as it is, it is a great opportunity to learn some fundamental copyright issues.

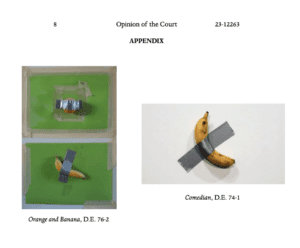

In this case, Joe Morford duct taped a banana and an orange to a wall and called it “art.” See right. Some time later, Maurizio Cattelan much more famously, for some reason, duct taped a banana to a wall, called it “art” and got paid $100,000 by some imbecile. Morford sued Cattelan for copyright infringement and lost, and now the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed that loss. See Morford v. Cattelan (11th Cir. Unpub. 2024).

Here’s the thing about copyright – it doesn’t protect ideas, it protects expression. Copyright rewards creativity and creation of original works, while it restricts actual copying. It doesn’t restrict your ability to come up with the same thing as someone else, as long as you do so independently.

The expression has to be original enough to be copyright protectable. For example, a foundational case Feist Publications, Inc., v. Rural Telephone Service Co., 499 U.S. 340 (1991) established that information alone without a minimal creative spark is not sufficient for copyright protection. That case dealt with just listing names and numbers in the phone book. In the Banana Case, the issue of copyrightability was not addressed by the court. However, it probably should have been.

The dispositive issue was whether there was copying at all.

You can show that a work was copied through direct evidence, or that there is indirect evidence of access to the original, or even just striking similarity. In this case, there was no direct evidence that Mr. Cattelan directly copied Morford’s original “Fruit Art” (and I stretch the definition of the word “original” here). Morford then relied on circumstantial evidence of “access” — showing that his “original” had been published on the internet for years, and thus Cattelan must have at some point seen it, before he came up with his “work” of taping a banana to the wall. That didn’t work either, because it was too speculative to say that Cattelan had to have seen this work of total genius on the internet before he had his “creative spark.”

So we come to the final fallback position – “striking similarity.” If there are infinite monkeys typing on infinite typewriters, one of them will type out “Hamlet” with precisely the same words used by Shakespeare. However, outside of the theoretical world, this does not really happen. Accordingly, when there are two works that are so alike that the later one must have copied the first one, courts will often infer copying. “A striking similarity exists where the similarity in appearance between two works is ‘so great it precludes the possibility of coincidence, independent creation or common source.’” (Op. at 6). But, courts are not slaves to similarity.

“But even “identical expression does not necessarily constitute infringement.” Calhoun, 298 F.3d at 1232 & n.9. Cf. Orig. Appalachian Artworks, Inc. v. Toy Loft, Inc., 684 F.2d 821, 829 n.11 (11th Cir. 1982) (cautioning district courts “not to be swayed by the fact that two works embody similar or even identical ideas”)”.

Although the expression in the two “works” is almost identical, the court said that there were “sufficient differences in the two displays to preclude a finding of striking similarity.” (Op. at 7). The court held that since there was an orange in the original, and not one in the alleged copy, that showed significant differences.

The result of this case is that there is no infringement here. However, I think the court’s reasoning was sloppy, and I think they knew it – which is why the case is designated as unpublished.

If we accept that the original work is sufficiently creative to warrant copyright protection at all, then I fail to see how deleting the orange from the original means that the two are not similar. They most certainly are “strikingly similar.” Had I decided this case, I would have ended it on the copyrightability prong – that our copyright laws are not so broad as to encompass the “creativity” involved in sticking a piece of duct tape over a banana. Lacking that creative spark, the work would be unprotectable, and then the court would not have had to jump to the somewhat lazy conclusion that the removal of the orange (and perhaps the green background) renders the works different enough that there is no copying at all.

I sincerely believe that Cattelan came up with his dumb idea independently of Mr. Morford’s dumb idea. Two idiots can come up with the same dumb thing at the same time, especially if neither is using enough of a creative spark to ignite the flame of copyright protectability.

In the end, we have a decision that might help you learn more about copyright law, but doesn’t do much to actually clarify the law in the Circuit, because the decision is unpublished and focuses on the wrong elements.